Parthenope is not the most known of the Sirens.

The myth regarding the Sirens gives them different name depending on the author: Pseudo-Apollodorus mentions Peisinoe, Aglaope and Thelxiepeia, others name Terpsichore, Melpomene and Sterope or Chthon, Homer does not give them any name. Their very number varies between two and five. The myth naming them as Leucosia, Ligeia and Parthenope (“virgin-voice”) is thus just one among many but, as it happens, is the one I am most interested in.

In my novels Parthenope herself tells her tale. It is worth noticing that, with her sister, she was transformed in a bird-woman (not a fish-maiden as the medieval traditions tell) by Demetra's wrath, as she was unable to protect her daughter Persephone from Hades' lust. Actually Hades even behaved as a gentleman: he was really in love with Persephone, he married her and made so that she could not have stayed far from him. At any new fall the maiden has to get back to her husband, whilst she could spend spring and summer with her mother to till the fields.

The temptation to explain here the chtonian meanings of the myth is strong, but this is not the time. If you wish so, I will be glad to prepare another post. Now I have to get back to Parthenope.

So, a bird-woman. Do we have images of that?

The one shown here is the reproduction of an attic vase dated to 470-480 BC found in Vulci and shown at British Museum, depicting Ulysses tempted by the Sirens. To be fair, they don't look so much alluring…

A more plastic image can be found at Athens National Archaeological Museum.

The second image is a funerary statue found at the Ceramics Necropolis in Athens. It was set next to the tomstone of Dexileos, an Athenian warrior, dead in 394-393 BC, and depicts the Siren while laments the dead, playing a lyre made of a tortoise shell. Feather and other parts were brightly painted.

Do we have other images and, most importantly, do we have images of our own Parthenope? Along with pottery, a wonderful research tool used by historians is the coinage and, at the time of the facts told in Neapolis - The Siren's Recall Neapolis was the mint in 200 miles around. But I will not add details you can find in the novel.

So, guess what you see on the coins from Neapolis at that time: very often, Parthenope's face. The nicest example I found is the one I use in the blog's header, but it is interesting to see if there were variations with time.

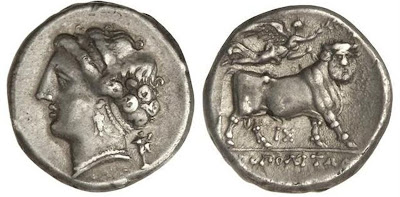

The coin depicted above here is the typical didrachm (two drachms) used in Neapolis between 340 and 241 BC (no euro adoptions for very long times, back then). I will not analyse here all the other elements but Parthenope's face, on the “head”, a bit plumpy (every age has its own beauty canons), the rich hairstyle held by a diadem, indicating the religious level of the character, and the noticeable jewels.

From the same time is this other didrachm depicting the same motif as the previous one. Yet, it is interesting to see that the model used to lend her face to Parthenope is different, thinner in her face, and with a more typically Greek nose.

As much Greek is the face depicted on this silver nomos, dated c. 300 BC. The detail level in this coin is really exquisite, and on the background of Parthenope's face you can see dolphins, declaring the absolute control of the polis over the sea.

And let's finally come to the coin I used for the blog's header. It is a stater dated to between 300 and 275 BC. After the head, at the base of the neck, what looks like a small scratch is told to be Artemis (by the letters ΑΡΤΕ below Parthenope's neck), also recognizable because of her dynamic pose, because she is holding bow and arrows, and by the dress (yep, Artemis was a bit of a tomboy).

What are all these elements telling us? First of all, the diadem in her hair is a sign of sacred recognition, and indeed we know by historical documentation that Parthenope was the protecting goddess of the polis. Better, as she is depicted on the coins, she is the very polis!

Then there are the jewels, showing wealth, so that we can at least tell that there was a sense of a pride linked with wealth. Also the juvenile face, seldom round, shows prosperity.

The traits, with that nose with no bridge, witness an noticeable affection to the Greek canons. To establish if that affection indicates a true and constant Greek presence on the territory or a fashionable imitation of imported canons, I am following this reasoning: as they are universal, canons are also immutable, so the idea of beauty changes very slowly in a society not experiencing changes and, when it experiences them, it follows them. The great changes lived in Neapolis between the IV and III century BC were the introduction of Samnites in the town society and, after 326 BC, the alliance with Rome. The first event allowed introducing new face traits within the citizenship, though they cannot be seen in the coins, though different faces can be seen on the same coins within a well-defined time span. We can thus clearly say that not only the canon was follwed, but that it emplyed for its own expression the continuous observation of Greek traits, strongly present in the town.

If you think this post was interesting, despite its length, and want to spend a nice day with other artefacts of that time, if you have not done that yet, may I advise a visit to the reknown Naples' Archaeological National Museum (MANN). I am sure that the visit will be an unforgettable experience!

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

More about Nymphius the Neapolitan

Plutarch is not the only historian to tell us about Nypsius the Neapolitan . Diodorus Siculus is often mentioned in his stead as the main so...

-

Parthenope is not the most known of the Sirens. The myth regarding the Sirens gives them different name depending on the author: Pseudo-Ap...

-

This blog is the English version of the one I have been editing since 2012 in Italian and that was intended as a logbook describing the wor...

-

Campania always was a meeting point for different cultures, and in IV century BC things were not different. Oscans/Samnites were perhaps th...

No comments:

Post a Comment